REVIEW: Five HUNGRY Reads

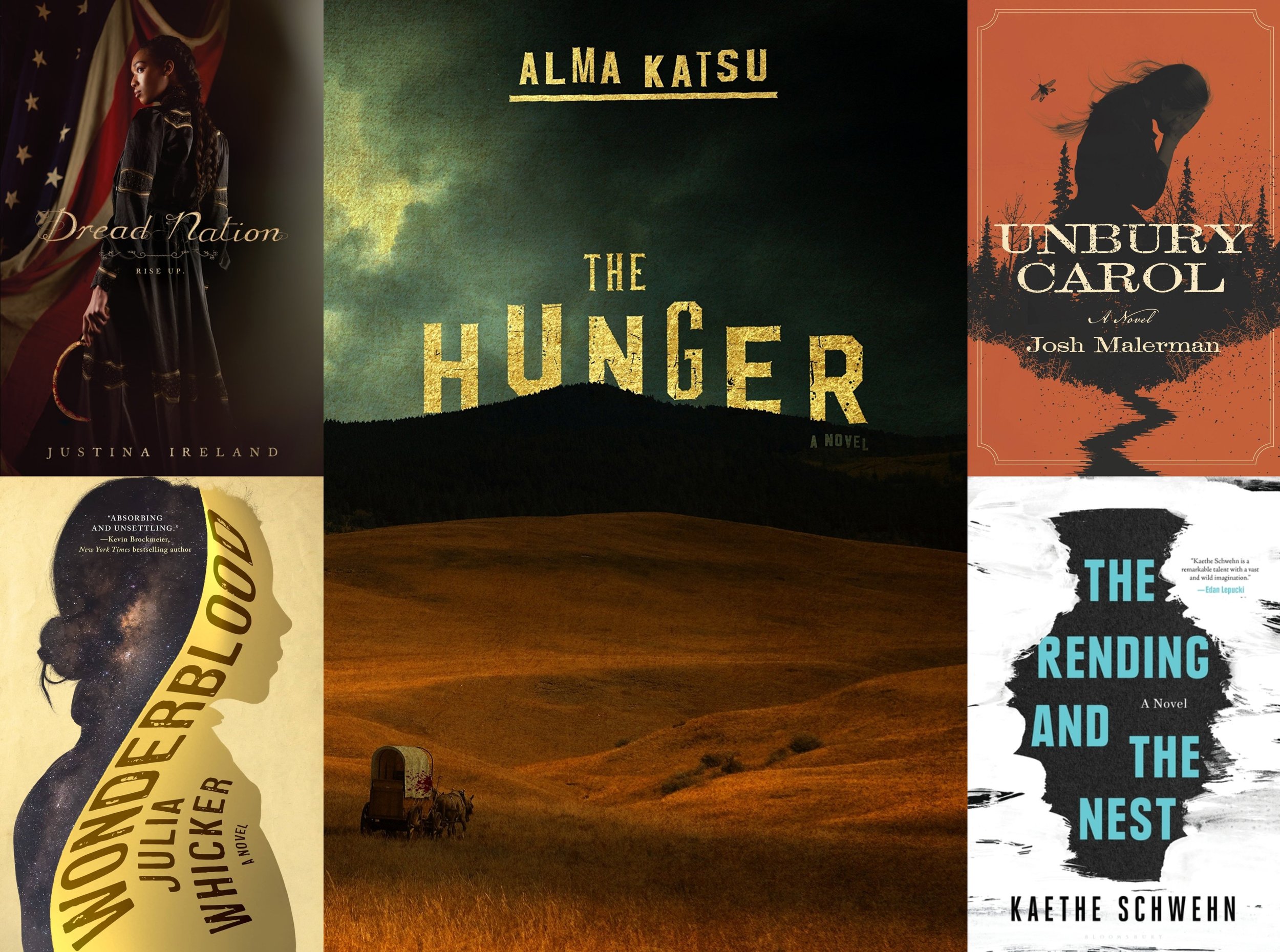

KEND

2018 has been marked by a series of science fictional explorations of hunger—both as a function of the undead trope and as a function of coming of age in a world determined to cut people, especially women, down. This review tackles five 2018 releases which all exist in conversation with each other: Justina Ireland’s breakout YA hit, Dread Nation; Julia Whicker’s Wonderblood; Alma Katsu’s take on the Donner Party, The Hunger; Josh Malerman’s Unbury Carol; and Kaethe Schwehn’s The Rending and the Nest. Not all of these books are like each other, but they all interrogate the role of hunger—physical hunger, sexual hunger, the hunger to prove oneself, and/or the body as a thing which has its own agency—and the symbolic power of consumption. There's something at work here, and perhaps you'll help me puzzle it out: some back-door conversation between the female body and hunger and danger.

*****

Let's start, as we always should, with zombies. Dread Nation is a winsome combination, mashing up the more traditional elements of a good zombie flick with social commentary on the Antebellum South. The events of this book take place in an alternate version of our own historical past, a few years past what would have been the Civil War if, you know, zombies hadn't happened. This is a book that requires little commentary from me, having become a raging commercial success even before dust jacket met shelf. The fact that my library had it on pre-order despite being an unproven debut and a young adult book that crosses genre categories (two marks against it, at least in terms of our library's current collection development strategy) tells you something about its widespread popularity. If you haven't already read this book, it's through no fault of the publishing industry's marketing strategy. More likely you're like me, and leery of books which ride in on a wave of popular acclaim and often ride out just as quickly.

What compelled me to read this book, then? The recommendation of friends I trust. The realization that Justina Ireland is not just another white, middle-aged male author taking an unearned stab at a glamorous, brocade-and-brimstone Civil War epic. (We've heard so much from white, middle-aged male authors about the Civil War as to complete co-opt the real and grim historical struggles of people of color to last us a lifetime. Or more. How about the lifetime of our planet? If we could just stop, that would be great.) I'm losing my grasp of what does and does not qualify as #OwnVoices literature—do you have to live through a thing to qualify?—but if anyone gets to use that hashtag about a zombie uprising in the close-post-Antebellum South, it's Justina Ireland. I'm incredibly excited that authors like Justina Ireland and Tomi Adeyemi are being well-treated by the traditional publishing industry, and raking in the movie deals. It's about damn time.

Dread Nation is so entirely deserving of the acclaim it has received. Jane McKeene is an excellent hero, her friends are excellent friends, and the twists and turns through which the plot drags readers kicking and screaming are, as far as I'm aware, unique in young adult literature right now. There are the requisite faults of all first installments of young adult series these days; many of the book's loose ends remain flapping in the wind, awaiting a second or third or even a fourth novel to tie them up. I'm beginning to realize that these books may look like novels, but they're really just the first chapter of a complete story, and expectations must be adjusted accordingly. The sheer pleasure of watching a young woman of color kicking zombie ass is enough to keep me invested, and for her to do so in clean prose and in the company of other interesting characters is a delight. Far more concerning than any structural flaws is the book's flawed treatment of Native Americans, thoroughly and gracefully addressed by Dr. Debbie Reese, founder of American Indians in Children's Literature and ALA's 2019 Arbuthnot Lecturer, in her Twitter feed. I can't recommend reading the whole Twitter thread enough, which Reese later blogged in its entirety; I found it revelatory.

Now, Ireland didn't intend to mis-treat Native American history in Dread Nation. After Reese's tweetstorm, she and Ireland began a conversation on the subject, although the details don't seem to be publicly available. That said, when a book that is touted for its strengths in representation of one underrepresented group throws another group under the proverbial bus, I'm automatically cautious. In the end, Dread Nation is a great read that should, as all books should, be contextualized within active conversations about diversity and equitable representation, deep research, and the ethics of fiction. I recommend pairing Dread Nation with another recent, fantastical work of young adult literature more true to the Native American experience: Rebecca Roanhorse's Trail of Lightning, as well as these recommendations from Debbie Reese, as found on the AICL website. While Dread Nation may appeal to those who loved Carrie Ryan's The Forest of Hands and Teeth, it's also the perfect entertainment vehicle for young activists and lovers of historical fantasy.

*****

Wonderblood by Julia Whicker takes a different angle on the zombie apocalypse, and seems much more strongly influenced by quote-on-quote "literary dystopias" like Emily St. John Mandel's Station Eleven and Margaret Atwood's Oryx and Crake than postapocalyptic zombie headliners like AMC's The Walking Dead (and the comics it's based on) or Max Brooks' World War Z. Taking this "literary" approach seems to be all the rage right now, a trend with which I've made my peace. After all, it's introducing untold numbers of literary fiction lovers to the science fiction and fantasy genres, even if it's under the false pretenses that science fiction and fantasy weren't already being written by authors with serious literary chops.

Unlike Dread Nation, which gives zombies pride of place as a serious threat and important plot device, Wonderblood utilizes the zombielike "Bent Head" virus/prion as a way to "clear the field" or "blank the slate" and therefore set the stage for the book's primary story arc. The virus/prion renders certain stretches of land unsafe to cross, in that it has gotten into the soil and can therefore be stirred up by passing travelers. In this postapocalyptic work, Whicker blends genres, leaving it unclear whether or not the magic, prophecy, and blood sacrifices enacted by the world's surviving inhabitants is actually effective. Many of them certainly seem to think so, but Whicker's claustrophobically tight point of view narration leaves no room for an objective observer. Rich paragraphs of lush description distract—or perhaps highlight, in places—the unremittingly grim reality of this world, which has been stripped of its beauties and rendered ponderous by too light of an editorial hand. Marketed as an expansive journey narrative featuring queens and Cape Canaveral, Wonderblood actually came across as a messy amalgamation from which I was able to draw little pleasure. Perhaps it was the sheer repulsiveness of the predators who stalk through Wonderland that put me off; here are men who are more than willing to prey on underage girls, and women who are more or less defined by their traumas. These are realities in our world today, but that doesn't make for a pleasant read. In fact, it acted as a most profound trigger for me, a bundle of sick feelings wrapped up in a sickly-sweet skein of words. The hungers here are perverse and exploitative, rooted in viscera and women's bodies: bodies subject to rape and illness. It doesn't help that certain characters are defined by their weight, which is exploited in vivid detail by Whicker for visceral impact.

Yes, Whicker can write. Her sentences are, objectively, gorgeous. If only I had emerged from this book without a shudder of deep revulsion.

*****

By far the most overt in its treatment of hunger as both symbolic and literal is Alma Katsu's historical reimagining of the Donner Party's fated trip through the American West, The Hunger. The events are more or less common knowledge, thanks to the size of the party and the fact that there were, in fact, survivors whose tales were well-documented in the popular literature of the time. If you've read the Donner Party's Wikipedia page or taken an American History class, there's no way to "spoil" this book for you. In that sense, along with many others, this book is reminiscent of Dan Simmons' The Terror, which was recently adapted into a most pleasurably horrifying show by AMC. If you've seen or read The Terror, then the language and the themes of The Hunger will make a kind of terrible sense, despite the historical events sharing little to no similarities whatsoever. Apart from the cannibalism.

Yeah, you should probably know about that, at least a little. The Terror ought to come with a trigger warning which includes "may/definitely contain/s scenes in which people actually eat other people on screen off of china plates," whereas The Hunger relies on a much more stealthy, diagonal approach to the subject. But in both books, the consumption of others serves as a stand-in for the annihilation of the self, and the subsumation of the individual within the collective panic of an isolated group of people at risk of being eaten by the scenery.

So much for comparison; The Hunger stands on its own legs, thematically as well as in respect to originality. Here, women occupy significant page-space, both as point-of-view characters and as the objects of others' thoughts. Katsu links the animal—as in, the animal instinct—with the diseased and the sexual, particularly depraved sexual behaviors as judged through the eyes of Christian and Mormon emigrants. Katsu's execution is nuanced and complicated enough to have kept me invested despite my discomfort with the problematically well-trod territory, and I appreciated the fact that women were not sapped entirely of agency in the name of "historical accuracy" (which is mostly a bullshit excuse for perpetuating an exploitative contemporary male gaze, anyway). I appreciated Katsu's incredible sentence work. I appreciated the fact that I was unable to sleep at all while reading this book, and not because I was kept up by some critical argument in my head. Katsu's work is genuinely haunting, and disturbing, and worth your time.

If you can handle cannibalism.

*****

Like Wonderblood, Kaethe Schwehn's The Rending and the Nest is mostly a story of what comes after. After disaster, after loss, after the world is wiped mostly (but not entirely) clean of its human residents. In point of fact, of all of the books one might compare The Rending and the Nest to, Wonderblood makes the finest and most proximate comparison. Both center on female characters who behave in unpredictable ways according to their own obscure reasonings, and who struggle to relate to the women around them, despite those female-to-female relationships being critical to their own self-definition. ("I am not her, therefore I am ....") Both involve bizarre new social orders constructed in the aftermath of absence, an absence manufactured by some sort of strange quasi-scientific, quasi-mysterious event. In Wonderblood, the apocalypse came in the form of a virus/prion; in The Rending and the Nest, the apocalypse comes quietly, with a mass disappearance of people coupled with a sudden appearance of giant piles of their disordered possessions. The survivors scrape by through plundering the piles—and the surrounding landscape—for pieces of peoples' lives from which they hope to reconstruct some kind of meaning, or by resolutely rejecting meaning altogether.

Then the pregnancies start. And boy, howdy, is that where shit gets weird. In this strange, possibly alien future, women give birth to everything (and the kitchen sink) except actual babies. A vase, decorative birds, and absolutely nothing human. The prose doesn't let us get wrapped up in the pregnancies themselves, but instead sweeps in routinely to remind readers that Schwehn is only interested in dealing with pregnancy, birth, and children as symbolic states of being. Her language is more Miéville than Whicker, more evocative of the Weird and the unsettling than of traditionally coherent dystopias. This is not a book for lovers of (quote-on-quote) "hard" science fiction or epic fantasy, but for poets and acolytes of the horrifying Weird.

It is, sadly, not at all a book for me, Kend. As with many (if not most) of the hungry books of 2018, The Rending and the Nest is Weird without leaving room for the queer, and for the Queer. The role of Woman and all that is symbolic about her various stoppered states of being are deliberated on in extravagant prose, but the tropes are still lying in wait just under the surface: the womb as a production engine of great horrors and great beauties, pregnancy and birth as passages to the revelation of selfhood and identity, humans as animals like any other. By the time Schwehn took her characters to a zoo in which people make a living by putting themselves on display for others, I had already suspected that the only symbols that were going to be interrogated were those of Woman as Mother and Lover and Innocent and Harlot. (Ah, those archetypes always failed me, even before I was equipped with the words nonbinary and agender and queer.) Unlike The Power, The Rending and the Nest doesn't acknowledge the intersection of feminism and the queer, much less their historic entanglement. I was left, perhaps appropriately, hungry for something more substantial—and more inclusive in its scope.

*****

Now, as we step down the last stair from our stack of grim postapocalyptic and historically revisionist narratives, we come to Josh Malerman's Unbury Carol. Of all of the zombie-ish narratives published in 2018, this is the least like what you're expecting. The best I can do to convey the tone is to say it's a tonal mashup of Neil Gaiman's Stardust with Genevieve Cogman's Invisible Library series with something Seanan McGuire might write with some sort of feminist highwayman take I haven't stumbled across yet.

So why is this included in the list?

Because Carol Evers is undead. Technically. As in, she routinely falls into comas which are indistinguishable from death to an external observer, and eventually ... reanimates. She doesn't have a craving for human flesh or anything, and she's actually incredibly vulnerable to exploitation by others (go figure, men are mostly awful), so this isn't your typical zombie narrative but instead a thoughtful exploration of what a spirited woman locked in an unresponsive body might think and feel while she's out of commission—and how the men in her life respond. Carol's point of view entwines with that of her husband, a no-good gold-digger looking to steal her money once he knows the truth about her "weakness," that of her former lover, retired highwayman James Moxie who shares less in common with Robin Hood than he does with an actual stagecoach robber, and that of an assassin and illusionist who has been hired to prevent the highwayman from saving Carol. The stories operate in pairs, with Carol's story running counter to her husband's, and Moxie's running counter to the assassin's. Each is on a quest—to outsmart the community, to overcome an incapacity, to honor a past romance, and to finish an unexpectedly challenging job.

The hungers here make for a nice change from the more ... literal ... hungers of the other hungry books of 2018; they're so subtle you might miss them in the general rambunctious adventures of the various characters. They're hungers for selfhood, and the chance to prove oneself. They're hungers for recognition and for the comforts of a normal life. And yes, Malerman tucks in story beats about exploitations and attractions, but they're not the primal urges of Katsu's The Hunger or the zombies in Dread Nation. There's always at least a thin veneer of civility to drape over the events of Unbury Carol, evoking something attitudinally similar to Georgian England even though the book is fully unstuck in time and place. The road runs through some kind of forest and stops off at some kind of town every now and then, and is populated by some kinds of people—but it could be any road in the English-speaking world, and any cluster of towns in a pseudo-Georgian American West. If it sounds like a combination that doesn't work, well, it occasionally doesn't ... but most of the time it really, truly does. And it makes for a perfect, upbeat palate-cleanser after a full roster of heavily-ornamented takes on hunger.

*****

That's it for the hungry books of 2018 (to date)! I'll be back soon with a review of more, shall we say, royal books released in the first half of 2018 soon.